I moved to Utah about 3 years ago. I grew up in Boise. There are mountains there, but compared to the Wasatch they are mostly foothills. I spent my youth backpacking some amazing Idaho ranges like the Sawtooths and White Clouds, but that was all I did: backpacked. The idea of “mountain climbing” was a bit abstract and foreign.

I didn’t realize that regular people climbed mountains everyday. I didn’t realized that regular people jam their hands in to small cracks and close their minds to the fact that falling on a cam or small nut they placed below could be fatal, but do it anyway.

The idea of mountaineering and rock climbing is still foreign to me. Since moving to Salt Lake I have climbed several peaks in the Wasatch, the Pacific Northwest, California, Colorado, Montana, and Wyoming, and I still can’t explain the feeling of it to others, unless they’ve already experienced it themselves. At that point, there isn’t much communication or explanation on its validity. It’s just a mutual understanding.

The idea of mountaineering and rock climbing is still foreign to me. Since moving to Salt Lake I have climbed several peaks in the Wasatch, the Pacific Northwest, California, Colorado, Montana, and Wyoming, and I still can’t explain the feeling of it to others, unless they’ve already experienced it themselves. At that point, there isn’t much communication or explanation on its validity. It’s just a mutual understanding.

Although I have a difficult time explaining it, I will give it a try in this post because I found a new relationship between mountain climbing and trad climbing.

I’d like to start by saying that am not a trad climber. I can, however, confidently say that I am a sport climber. I love sport climbing. I enjoy the rush of holding a crimp above a bolt and going through that mental process of dealing with the possibility of a fall and deciding to make a move anyway.

I feel like most trad and big wall climbers would agree that sport climbing is not within the same realm. It’s fairly easy to understand why. Climbing bolted routes is one of the safest ways to climb vs climbing on and placing your own gear which requires greater confidence and trust in your abilities.

On the other hand…

Mountaineering is difficult in a few different ways, depending how long and technical the route to the top is. It is also dependent on time of year, whether glaciers are involved, and how popular/well-traveled the trail is. The more experience you gain, the more your comfort zone expands, and the more you are able to push your boundaries. So, one route may be very difficult for one, and a walk in the park for another.

The boundary of a person’s comfort zone can depend on a lot of different things and usually is conditional to a climber’s experience in that specific area. No matter where you stand in terms confidence, when you cross outside of your comfort zone, the feeling of the adventure changes.

The boundary of a person’s comfort zone can depend on a lot of different things and usually is conditional to a climber’s experience in that specific area. No matter where you stand in terms confidence, when you cross outside of your comfort zone, the feeling of the adventure changes.

It is during the time outside of your comfort zone where it begins to expand and things that seemed impossible before, now are possible because you are in the process of accomplishing them. You begin to realize that you are capable of more than you thought and even though you may be freaking out in your mind, your heart is pounding, and your mouth is dry, you push through and achieve your goal.

When you are finished, you return to your car, tent, home, hut, or wherever “done” is. You sit down, let your shoulders relax, and take a deep breath. It may have been 4 hours, 12 hours, 24 hours or 5 days outside of your comfort zone. You may have crossed 20 miles, gained 6000 vertical feet or been relying on nothing more than your cam placements on a hand crack up a 600 foot wall.

After its over. You think back on the experience. You remember how crazy it was, but all the horrible parts start to disappear. You look back and think only of success. The moments where you were closing your eyes and thinking “why did I come on this adventure?” are now answered as you sink back into your comfort zone.

The difficulty of long days or multiple days in the mountains in pursuit of a summit provide you with moments of pure exhaustion where you question yourself and your motivation. When you have been hiking for 18 hours straight and you look up at the stars and wonder why you do this to yourself again and again.

The difficulty of long days or multiple days in the mountains in pursuit of a summit provide you with moments of pure exhaustion where you question yourself and your motivation. When you have been hiking for 18 hours straight and you look up at the stars and wonder why you do this to yourself again and again.

But when you get back home, you ache for that feeling again. It is the feeling of living and pushing yourself to edge. It is in these moments that you learn more about yourself than you ever have. And it is these moments that make it impossible to explain to others why you climb.

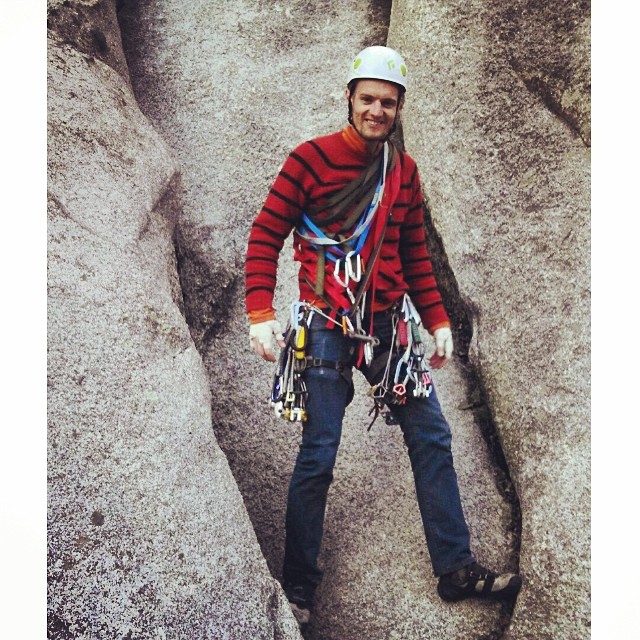

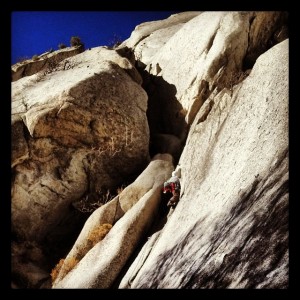

I found a similar feeling with trad climbing, I had the privilege of climbing Crescent Crack in Little Cottonwood Canyon a few weeks ago. It’s a nice starter trad climb, but it took us a long time to do the 2 pitches. This was mostly due to lack of experience and poor rope management.

The climb began around 1:30pm and I led the first pitch. We had all taken turns climbing the first pitch a few weeks earlier, so the route was a little familiar.

One main issued was limited gear. I reached a crux section of the climb just below the chain anchors. I did not have adequate protection and didn’t feel confident making an intense move with the possibility of decking on the ledge about 15 feet below.

I returned to a set of anchors on the ledge below and two of my partners followed and cleaned, bringing a second rope. We learned here how much longer it takes to climb a route with 3 people instead of just 2.

Another team of climbers decided it would be a good idea to climb the route in between one of our climbers. so we waited for them to pass us, but they made several mistakes of their own and ended up having to down climb and rappel several different times. This took ages. By the time our team was at the off-width start of the 2nd pitch and actually climbing it was after 6pm.

Wes made his was up the 2nd pitch and after building his own anchor belay station, finally found the chain anchors at the bottom of the ramp traverse. He moved to them as set up belay. At this point, our other partner, Kirk, decided it would take too long to finish and rappelled down just as I began up the second pitch. I climbed, cleaning gear out of the crack as I went.

Wes made his was up the 2nd pitch and after building his own anchor belay station, finally found the chain anchors at the bottom of the ramp traverse. He moved to them as set up belay. At this point, our other partner, Kirk, decided it would take too long to finish and rappelled down just as I began up the second pitch. I climbed, cleaning gear out of the crack as I went.

I traversed the ramp with rope above me through a piton that may or may not be trustworthy of saving my life if I slipped. I reached Wes as the sun sank behind the horizon to the West.

In the dull light we laughed at how much time we wasted and how ridiculously long it took us. I had never rappelled in the dark and used to see headlamps of people high on the cliffs of Little Cottonwood from the road. I’d think to myself, “those guys are crazy.”

I expected that I would be nervous in the dark because the sun provides so much more mental strength than the night, but there was no problem. I felt confident in my partner’s and my own abilities to make it down safely.

When we reached the parking lot, I sat in my car and played out the experience in my mind. There were a few moments leading the first pitch and just before starting up the 2nd and I thought we might run out of daylight where I felt the adrenaline kick in and started thinking to myself, “what did I get myself into.”

Safe in my car, I was glad to look back on the previous few hours and laugh at how my comfort zone expanded and I knew I was capable of new things.

Safe in my car, I was glad to look back on the previous few hours and laugh at how my comfort zone expanded and I knew I was capable of new things.

As you expand the area where you feel comfortable, your adventures begin to change. Over the passed few years in Utah, an intense adventure has changed from an overnight backpacking trip up Bells Canyon, to climbing the tallest volcano in North America and leading a pitch of a 5.7 trad route.

3 years ago I never would have imagined I was capable of anything close to that, but the more you expose yourself to things that frighten you, the less frightening they become. And that is why I rock climb and mountaineer.

You must be logged in to post a comment.